The Doctor-Patient Relationship: When Patients Do Not Tell the Truth

Hippocrates told his medical students and interns in 400 B.C. to “keep watch also on the faults of the patients which often make them lie about the taking of things prescribed.”1 Doctor Gregory House in the popular medical television series House said, “If you want an accurate patient history, don’t ever talk to the patient. Everybody lies.”2

Face-to-face meetings between doctors and patients are a special time and part of a complex relationship that is not paralleled elsewhere. Nowhere else can someone discuss their thoughts, the personal details of their health, and the intimate aspects of their relationships to a professional who is trained to be objective and nonjudgmental. Rarely do individuals experience a relationship with another person that allows such a degree of invasiveness and examination of their psyche, cognition, emotions, social, and physical functioning.

There are many expectations that accompany this relationship, both from the clinician’s perspective and the patient’s point of view. A patient who does not like, trust, or respect the clinician may not disclose complete information about themselves or their symptoms. A patient who is anxious may not clearly comprehend information, for example. The relationship therefore directly determines the quality of information elicited and how well it is understood. It is a major influence on practitioner and patient satisfaction and often determines compliance with treatment (i.e., adherence).3 In order for this relationship to work well, mutual trust and open communication are essential elements, but these elements are not always present because the medical encounter can present a number of barriers to patients and clinicians.

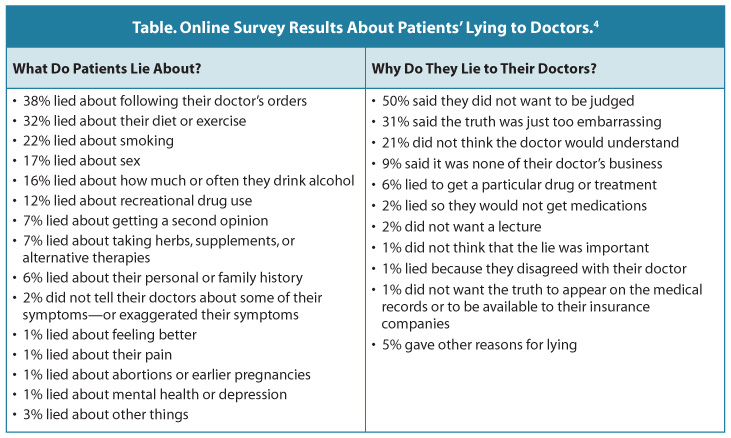

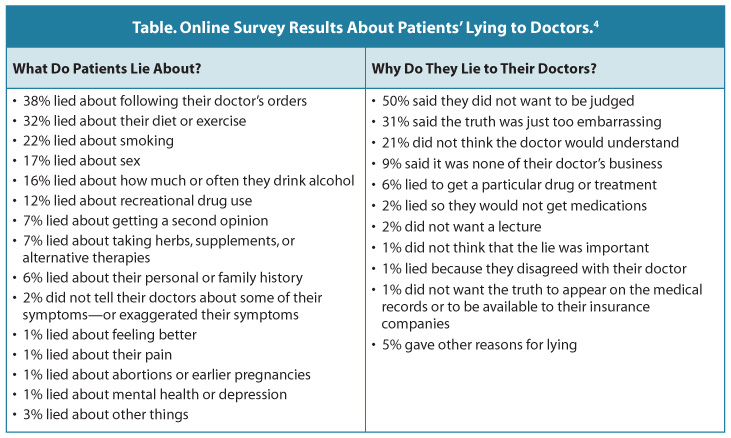

Patients Lie to Their DoctorsAn online health survey on WebMD4 asked approximately 1,500 website visitors about lying to their doctors. Patients were asked two questions about lying—what they lie about and why they lie about it (see Table). In the survey, younger patients (i.e., aged 25 – 34) were more likely to lie to their doctors than were patients aged 55 and older. Younger patients were more likely to lie about recreational drug use, sexual history, and smoking than older patients were. Men and women tended to lie about the same things, with the exception of drinking. Men are significantly more likely than women to lie about how much they drink: 24% vs. 15%.

When the surveyors consulted psychiatrist and ethicist Robert Klitzman, MD, Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Mailman School of Public Health, about the results of the survey, Klitzman pointed out that most lies are about “taboo areas” such as adherence to treatment, substance abuse, or sexual behavior. Other areas are fear that their conditions may influence insurance companies or employment; further, some patients will even exaggerate their illness to get prompt medical attention.5 “A number of studies have tried to chronicle how much patients lie about complying with doctor’s orders. It’s an important area we don’t really know much about,” said Dr. Klitzman.6

A national survey of 3,146 adult smokers and former smokers in the United States revealed that 1 in 10 concealed their smoking habit from their doctors to avoid “getting a lecture” and feeling ashamed and stigmatized.7

Adherence: A Common Deception in MedicineIt is estimated that 30% – 60% of patients with chronic illnesses do not adhere to medical therapy, and that this can result in exacerbation of the illness, adverse effects, hospitalization, increased costs, and disease progression.8 Non-adherence is generally thought of as the failure to take medications consistently, a 2010 study of e-prescriptions reported that 22% were never filled. Patients frequently do not take medicines as prescribed and often do not communicate with their physicians about their medication-related behavior.9

The literature suggests various reasons for the lack of this discussion. Patients who keep silent may be a result of lack of trust in either the doctor or the choice of medication, or patients may fear provoking anger in the provider by admitting non-adherence.10 Questioning the provider is a risk for creating tension. One study found that patients were much less likely to take medication if beliefs and concerns that conflicted with their physicians’ beliefs were not addressed.11

An article on medication non-adherence was published online in The New York Times, in the Health section.12 Readers were encouraged to comment on the article, and Bezreh and colleagues conducted a qualitative content analysis of the online responses (130 comments by 117 unique participants).13 Two main themes emerged from the analysis of the comments related to adherence. The first was criticism and distrust of various elements of the health care system, including pharmaceutical companies, the United States Food and Drug Administration, insurance company practices, and affordability of medications. The second was a shift in the patient role toward self-reliance and self-protection.13

According to the researchers, implicit in many of the comments is an important redefinition of the traditional physician–patient relationship. “Some patients feel the onus is on them to double-check doctor recommendations, perform their own research, or decide how to make their care congruent with other demands of life including financial pressures. Others take this even further and appear to be using doctors as “consultants” whose advice they may ignore. Furthermore, it appears that the older model of how the physician and patient should interact are sometimes being replaced without explicit discussion and recognition that this is happening.”13

Tate14 describes the “rule of one-thirds” when it comes to patients’ abiding by medical advice:

So why is it that intelligent professionals, who work with patients on a daily basis, often for many years, cannot ascertain that a patient may be lying, acting deceptively, or just withholding information? Most professionals are less skilled in lie-detection than they think they are. Ekman and colleagues asked representatives from various professions to determine whether a woman on videotape was describing her emotions truthfully; these experts (psychiatrists, judges, police officers, and polygraph examiners) all performed no better than chance would predict them to perform.15 According to Palmieri and colleagues, “clinicians would benefit from and should be encouraged to rehearse different communication strategies and to seek supervision and consultation around matters that are challenging.” While patients clearly have a role in fostering honest communication with their providers, clinicians can help facilitate such interactions by being thoughtful, deliberate, and self-aware.16

The Evolving Role of the Doctor – Patient RelationshipFor over 5,000 years, the basic style of the doctor–patient relationship has been described in ethical jargon as “beneficent paternalism.” Tate states, “The medical profession has adopted a well-meaning parental role in most patient encounters. This role is taken for granted by our society, and produces recognizable patterns of behavior, which are disease-oriented with a tendency towards authoritarianism.”14 The patient’s role was to trust and to follow “doctor’s orders.”3

According to medical historian Edward Shorter, the post-World War II year of 1945 was a pivotal time for modern medicine. New drugs were discovered (antibiotics, sulfa, etc.) that transformed the practice of medicine, not so much in the use of these drugs as treatment but in establishing a new focus of science on microbiology, immunology, genetics, and biochemistry. This led medicine toward a mainly organic picture of disease. The battle was then between the doctor and the cause of the symptom or illness. The “‘biomedical” model came about, as did medicine’s diminished interest in the patient’s experience of illness. Shorter maintained that this “depersonalization” of medicine led to less interest in history and physical exams in favor of more objective data-collection and interpretation of laboratory results. The patient’s role was generally restricted to answering the questions asked. One manifestation of this shift in medicine was a reduction of time paid to emotion and its role in the care process.17 Shortened communication between doctors and patients unfortunately acts to restrict the many therapeutic purposes that communication is supposed to serve.

An OpEd column in The New York Times last year entitled “Decoding the God Complex” describes that “medical schools are starting to train doctors to be less intimidating to patients. And patients are starting to train themselves to be less intimidated by doctors.” The author continues that “there have been baby steps away from the Omniscient Doctor. The federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has begun a new campaign to encourage patients to ask more pertinent questions and to prod doctors to elicit more relevant answers.”18 Other agencies have also published “How to talk to your doctor” articles—among them, the American Medical Association19 and the National Institute on Aging.20

In the mid-1980s, health care began a “patient-centered” focus, which is defined as treating the patient “as a unique person with his or her own story to tell.” As part of this shift, the term “noncompliance,” which was seen as presuming a duty of obedience, was replaced by “non-adherence.”21 In the late 1990s, efforts to redefine the clinical relationship resulted in increased interest in a “shared decision-making” model that centers on having physicians and patients reaching agreement—via discussion that includes and respects the beliefs and wishes of the patient.22

Cushing and colleagues emphasize the importance of two-way communication in shared models of communication; however, they conclude that while progress is being made, it is far from the norm in the clinical relationship.23 It is interesting to note that the evolution toward shared decision-making models came when society had increased access to information about health and medicine. The Internet has given patients access to information that was once available only to health care professionals.24 While one may suggest that this access might lead to stronger doctor–patient relationships, access to health information can also increase awareness of doubts about treatment and differences of opinion about the management of illnesses, as well as difficulty in determining what information is valid, which can result in both deference toward and declining trust in the medical profession.25 The “experts” are always issuing guidelines, which are soon contradicted by another set of “experts.”18 According to Groopman and Hartzband, “The unsettling reality is that much of medicine still exists in a gray zone, where there is no black or white answer about when to treat or how to treat.”26

It’s All About CommunicationThe medical interview is the major medium of health care. Most of the medical encounter is spent in discussions between practitioner and patient.3 For the patient, the discussion that takes place in the visit gives meaning and legitimacy to feelings of concern and physical discomfort; sometimes, just giving a medical condition a name can make a patient feel more at ease with what they are feeling.3

“Through discussion, doctors and patients express who they are, what they expect from each other, and what kind of relationship they have. And open discussion can have powerful consequences. There are times that a patient’s very motivation to get well, can be seen as springing from the quality of the discussion with his or her doctor.”27 Without this level of interchange, the patient and doctor may never even reach a common understanding of the purpose and goal of the medical visit. Because of miscommunication during what may seem like a simple conversation, the routine medical visit often does not reach its therapeutic potential.27

Nobody goes to a doctor with just a symptom. They go with ideas about the symptom, with concerns about the symptom and with expectations related to the symptom.14

Goals of Communication14The basic communication goal, from a clinician’s perspective, is to ascertain why a patient has come for an appointment. While this may seem an obvious goal, research suggests that too often, ascertaining the patient’s reason for the appointment does not take place.14 In many clinical consultations, doctors and patients do not appear to be talking about the same thing. This can lead to a dysfunctional conversation in which the doctor and the patient are each pursuing their own, quite separate agendas. Doctors are good at establishing a diagnosis—including discovering the nature and history of the problem and its likely cause—but tend not to be good at finding out about a patient’s beliefs and expectations. This can not only interfere with the doctor-patient relationship but can also provide patients justification for concealing information.

|

Adapted from: Tate P. The Doctor’s Communication Handbook. 6th ed. Oxford, UK: Radcliff; 2010.14 |

Patients come to an appointment expecting that treatment will be uniquely suited to their individual needs, but the opportunity to express these needs must happen within the constraints of short appointments scheduled a few times throughout the year. It is within these limitations that patients attempt to establish their unique identities and tell their stories to the clinician … and hope that they are being heard and understood.27

Clinician’s Attention SpanIt is interesting to note that what the patient wishes to communicate is not limited to the first-presenting problem. “Patients often state a medical complaint as a ‘ticket of entry’ to medical care, even though the primary and most pressing concern may be unrelated to this complaint.”27 A study by Beckman and colleagues focused on the first 90 seconds of the medical visit, and found that the patient’s response to the physician’s opening question was completed in only 23% of the visits studied. In 69% of the visits, the physician interrupted the patient’s opening statement, after an average of only 15 seconds. In only one of these visits was the patient given the opportunity to return to, and complete, the opening statement. Of the 30% of patients who were allowed to continue, none of their statements took more than 2.5 minutes. Analysis of the issues raised by patients throughout the visit showed that the first-mentioned concern was no more clinically significant than other concerns that were expressed later, yet later concerns tended to be raised by patients in a more haphazard manner and received inconsistent attention from the physician.28 Fifteen years later, this study was replicated and it was found that little had changed in physicians’ attention to patients’ agendas. Patients’ initial statements of concern were completed in only 28% of interviews and their opening statements were redirected after an average of 23 seconds.29

“The Doorway Question”Often because of feelings of embarrassment, anxiety, or not wanting to sound foolish, patients’ “secondary” concerns may be hidden beneath the surface of what is believed to be “more legitimate” medical complaints. These unstated concerns are often referred to as the patient’s hidden agenda, and they are especially dreaded by physicians when they are brought up as the patient is leaving.30 The dreaded doorway question—for instance, “By the way doctor, I have this problem … but that’s nothing to worry about, right?”—can necessitate a time-consuming extension of the medical visit. White and colleagues estimated that 20% of routine primary care visits have a new problem introduced during the visit’s closing minutes.31 Marvel and colleagues found that the raising of concerns late in the visit was associated with failures to determine the patient’s agenda during the visit opening. The researchers found that patients were nearly twice as likely to introduce new concerns late in the session if the physician had not attempted to solicit the patient’s agenda at the beginning of the visit.29

Significance of SymptomsAnother important but often forgotten or overlooked element in clinician–patient communication is an exploration of the significance and impact of the illness or medical problem for the patient. How patients understand their symptoms or illnesses and the attributions that the patients make are extremely important in understanding their reactions and fears. Inordinate distress, for example, may stem more from a patient’s belief about what is wrong with them than from the disease itself.27

Most patients have a theory about what causes their symptoms or conditions. Understanding to what a patient attributes a particular symptom can be helpful, in that it may reveal some of the patient’s personal and emotional experiences, which in fact could be the reason for that office visit. Often patients may be reluctant to discuss their thoughts or ideas, for fear of appearing ignorant or foolish. The patient may have an incorrect medical explanation for the symptoms and may need education, or the patient may subscribe to religious or cultural beliefs that differ from the clinician’s understanding. Once these beliefs can be openly discussed, clinicians can work toward a resolution.27

Finally, patients may come to a clinical visit with specific expectations in mind, although they may be reluctant to make these known directly. Expectations may be for a particular treatment or, most commonly, simply for a better understanding of the etiology, diagnosis, or prognosis of the condition. They may know family or friends who have experienced a similar condition and may be concerned about how this may relate to or affect them.27

SummaryThe significance of doctor–patient communication goes beyond individual visits and personal discussions. It forms the foundation for a patient’s participation in the health care process, adherence to health care goals, knowledge about his or her medical condition, and general attitude about illness and health. Medical care is as much a social process as a technical one.27

According to Benjamin Disraeli, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”32 Even though over 8,000 articles, monographs, chapters, and books in modern medical literature have been written about doctor–patient relationships, too many uncertainties remain to be defined in understanding the scope of what can be right and wrong in the therapeutic relationship.3 Patients may withhold information for a variety of reasons. Are they lying to conceal information? Are they intimidated by the doctor–patient relationship? Is the structure of the medical encounter less than conducive to real communication than it should be? These are important considerations for clinicians to ponder, and it is time to rethink the clinical relationship and how it is evolving. Sir William Osler, MD, who has been called the “Father of modern medicine,” is quoted as saying, “Listen to your patient, he is telling you the diagnosis.”33

Oscar Wilde said of England and America that “we were divided by a common language.” The same could be said of doctors and patients.14

Clinical ConnectionsPost-Compass Questions™