|

Do You Know Who I Am? A Look at the Devastating Effects of Alzheimer's Disease - Strategies for Early Recognition and Treatment

by Christina J. Ansted, MPH

Hearing the word “dementia” usually conjures up thoughts of someone who is confused about their thoughts, memories and/or surroundings. Dementia is associated with getting old and with mental illness, but there remains confusion in the general public as to the differences between dementia, senility and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The definition of senile is a deterioration of mental or physical weakness. The term dementia refers to memory impairment and loss of other intellectual abilities, which interfere with normal daily activities. Alzheimer disease is the most common type of dementia, accounting for 50% to 70% of dementia cases,(1) followed by Lewy Body dementia (LBD). The correct term for Alzheimer's disease is “Senile Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type.”

Alzheimer’s disease was first identified by Dr. Alois Alzheimer in 1906. Today, it is the seventh-leading cause of death in the United States, with as many as 5.3 million Americans living with the disease.(2) The older population in 2030 is projected to be twice as large as in 2000, growing from 35 million to 71.5 million.(3) Delaying the onset of Alzheimer's disease in the United States by just two years, between now and 2050, the number of affected individuals would decline by 1.9 million. Researchers at Johns Hopkins used U.S. Census and mortality data to project the future prevalence of Alzheimer's disease. In 1997, an estimated 2.3 million Americans suffered from AD, with about 360,000 new cases diagnosed each year. By 2050, the rate of Alzheimer's is expected to almost quadruple, with the disease afflicting some 8.6 million Americans, one person in 45, with 1.1 million diagnoses each year.(4) These data point to the incredible impact this disease will continue to have on patients and families and the growing impact it will have on the United States healthcare system.

There are several factors that increase the risk for the development of dementia. The primary risk factor is of course age. As you get older your chances of developing dementia increases. Genetics can also play a role in the onset of Alzheimer’s, however most people with a family history of AD never go on to develop the disease. Gender also has an effect on susceptibility to AD. In post-menopausal women, the precipitous depletion of estrogens and progestogens is hypothesized to increase susceptibility to AD pathogenesis, a concept largely supported by epidemiological evidence, but refuted by some clinical findings.(5) Experimental evidence suggests that estrogens have numerous neuroprotective actions relevant to prevention of AD, in particular promotion of neuron viability and reduction of beta-amyloid accumulation, a critical factor in the initiation and progression of AD.(5) Normal age-related testosterone loss in men is associated with increased risk to several diseases including AD. Like estrogen, testosterone has been established as an endogenous neuroprotective factor that not only increases neuronal resilience against AD-related insults, but also reduces beta-amyloid accumulation.(5)

Other risk factors are more malleable. As with most illnesses, your risk of developing AD can be increased by smoking and alcohol use. Diet also plays a factor. Atherosclerosis, obesity, diabetes, alone or in combination, has been shown to increase the risk for AD. A previous head injury can increase your risk of developing AD in older age, as does lack of or fewer years of education. Long-term stress, anxiety and depression have been linked with an increased risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease. In fact, some research suggests that long-term stress stimulates the growth of the proteins that might cause Alzheimer's, which can lead to memory loss.(6) There is also evidence suggestive of a link between vitamin D deficiency and increased risk for AD. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] has been associated with increased risk for cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, depression, dental caries, osteoporosis, and periodontal disease, all of which are either considered risk factors for dementia or have preceded incidence of dementia.(7) It is important that healthcare providers, patients and families are aware of these risks and are discussing risk factors during regular patient visits.

A study just published by Patricia Boyle, PhD and colleagues found emerging evidence that people who have a sense of purpose in life have less risk of developing Alzheimer’s or even mild cognitive impairment (MCI).(8) "Alzheimer's disease is one of the most dreaded consequences of aging, and finding risk factors that we can modify to prevent or at least delay the disease is a top public health priority," said Patricia Boyle, PhD, principal investigator and a researcher in the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center.

Preventative factors that may protect against the development of Alzheimer’s disease include regular use of the brain through maintenance of cognitive activity, a healthy diet, and exercise. Brain exercises, and activities that keep the brain active, may delay memory decline and other dementia symptoms according to several recent studies. In fact, one recent study found that individuals with high mental stimulation actually had a 46 percent decreased risk of dementia. This effect was even maintained later in life, as long as the individuals continued to engage in brain exercises and other forms of mentally stimulating activities. Other aspects of a person’s lifestyle such as stress management, physical exercise and a balanced diet have also been linked to a decrease in dementia and Alzheimer’s symptoms.(9) A resource known as “The Online Brain Games Blog,” developed the 4 pillars of brain health,(10) provides an outline of activities to keep the brain healthy. Cognitive training (CT) may also be effective as a therapeutic strategy to prevent cognitive decline in older adults and particularly as a secondary prevention method for "at risk" groups.(11)

There is also increasing evidence to suggest that physical activity has a protective effect on brain functioning in older adults. To date, no randomized controlled trial (RCT) has shown that regular physical activity prevents dementia, but recent RCTs suggest an improvement of cognitive functioning in persons involved in aerobic programs, and evidence is accumulating to show the benefits of regular exercise and future prevention of Alzheimer disease may be linked to lifestyle habits such as physical activity.(12)

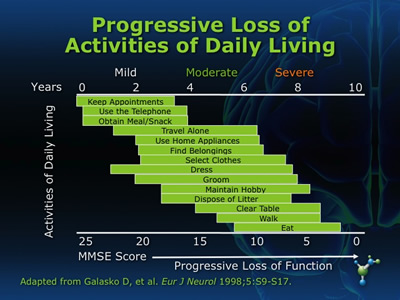

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that places substantial burden on family members who are providing support to patients with declining cognitive and functional abilities (see Figure 1). Many AD patients eventually require formal long-term care (LTC) services because of the absence, exhaustion, or inability of family members to provide care. Current evidence suggests that early pharmacological and caregiver interventions can delay entry into nursing homes and potentially reduce Medicaid costs.(13) Long-term treatment with galantamine or other AChEIs such as donepezil appears to be associated with a significant delay in the time to nursing home placement (NHP) in patients with AD and AD with cerebrovascular disease (CVD).(14,15) However, these cost savings are not being realized because many patients with AD are either not diagnosed or are diagnosed at late stages of the disease, and have no access to Medicare-funded caregiver support programs.(13)

Figure 1

The ability to recognize AD-related symptoms as distinct from normal age-related changes is paramount to the early and accurate diagnosis of this disease. The early recognition of AD can be problematic in patients residing in long-term care settings who do not have a preexisting diagnosis of dementia. Residents in LTC facilities generally have fewer day-to-day cognitive demands and, thus, nursing staff or caregivers may not recognize cognitive deficits until the disease is more advanced. Moreover, many nonspecialists may not differentiate AD symptoms from normal age-associated cognitive and functional impairments.

With such an insidious and silent disease, vigilance is our best defense. In an attempt to provide us with tools for recognition, the Alzheimer’s Association put together the top ten warning signs for AD:

Tools for assessment of a patient’s physical, functional, psychosocial, and cognitive status are available in standardized instruments such as the Minimum Data Set (MDS) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The MDS is part of a federally mandated process for clinical assessment of all residents in Medicare or Medicaid certified nursing facilities, and the MMSE is a brief, quantitative measure of cognitive status in adults. It can be used to screen for cognitive impairment, to estimate the severity of cognitive impairment at a given point in time, to follow the course of cognitive changes in an individual over time, and to document an individual's response to treatment. Utilizing these instruments systematically and consistently will result in improved diagnosis and management of AD and hopefully improved outcomes for patients.

Neuroimaging measures and chemical biomarkers may be important indices of clinical progression in normal aging and mild cognitive impairment and need to be evaluated longitudinally.(16) A new neuroimaging technique recently developed may soon have a profound impact on the identification of Alzheimer’s disease. Dr. Gil Rabinovici of the University of California-San Francisco's Memory and Aging Center says, “the new technique called "PIB-PET" has been found effective in detecting deposits of amyloid-beta protein plaques in the brains of living people, and it's such deposits that are predictive of who will develop Alzheimer's.” In current clinical practice, amyloid deposits (see Figure 2) are detected only on autopsy, but UCLA scientists and colleagues from UC Riverside and the Human BioMolecular Research Institute have found that a form of vitamin D (vitamin D3), together with a chemical found in turmeric spice called curcumin, may help stimulate the immune system to clear the brain of amyloid beta.(17,18,19) "We hope that vitamin D3 and curcumin, both naturally occurring nutrients, may offer new preventive and treatment possibilities for Alzheimer's disease," said Dr. Milan Fiala, study author and a researcher at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

Figure 2

There is also some evidence to suggest that there may soon be a test to confirm or rule-out the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. A team of Penn Medicine researchers, led by Leslie M. Shaw, PhD, Co-Director of the Penn Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) Biomarker Core, found evidence of neuron degeneration – marked by an increase in CSF concentration of tau proteins – and plaque deposition, indicated by a decrease in amyloid beta42 concentration. In addition, people with two copies of the genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease, apolipoprotein E (APOE) epsilon 4 allele (APOE ε4), had the lowest concentrations of amyloid beta42, compared to those with one or no copies.(20,21) "With this test, we can reliably detect and track the progression of Alzheimer's disease," said Dr. Shaw.

Onset of AD is gradual, with cognitive decline and deficits in short-term memory typically being the earliest indicators. In later stages of the disease, patients experience decreased overall function, have reduced capacity to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) (see figure 3), and frequently exhibit problem behaviors.

Figure 3

The phase between normal forgetfulness and dementia is know as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). While not everyone who has been identified as having MCI will go on to develop Alzheimer’s, MCI does present an increased risk for development of the disease; especially when dealing with symptoms of memory impairment.(22) A clinical tool used to screen for MCI can be found in the Computer-Administered Neuropsychological Screen for Mild Cognitive Impairment (CANS-MCI), of which clinical versions can be accessed at http://www.screen-inc.com. The CANS-MCI detects changes in cognitive ability within primary care facilities so that patients have a better chance of being responsive to early MCI treatment.(4)

Although not a form of dementia, MCI could be seen as a precursor to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Early onset Alzheimer’s is a term used to describe when Alzheimer’s strikes someone before the age of 65. Of all the people with Alzheimer's disease, only 5 to 10 percent develop symptoms before age 65. Early-onset Alzheimer's has been known to develop between ages 30 and 40, but more it is common to see in someone in his or her 50s.(23) Family history plays a more significant role with early-onset AD. Having grandparents or a grandparent and parent who both had early-onset AD that progressed to AD does increase the risk for developing AD. This increased risk is related to the APOE ε4 allele, however, at least one-third of people with AD do not have this form of the gene.(24) Four to seven other AD risk-factor genes may exist as well. One of them, SORL1, was discovered in 2007. Large-scale genetic research studies are looking for other risk-factor genes. For more information, see the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Fact Sheet.(24)

A primary sign for dementia is typically memory loss, but presentations with prominent cognitive impairment in other domains besides memory, like prominent apraxia, language problems, or executive dysfunction, may occur and are relatively more common in early-onset AD than in AD. Patients with early-onset AD often present with a non-memory phenotype, of which apraxia/visuospatial dysfunction is the most common presenting symptom. Atypical presentations of AD should be considered in the clinical differential diagnosis of early-onset dementia and physicians need education and tools to help guide them in this area.(25)

Evidence-based practice guidelines, such as the APA’s 2007 Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias (http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracGuideTopic_3.aspx) support early intervention with both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments. Reinforcing the importance of early intervention may help clinicians diminish the insidious course of this disease on their patients. The earlier the treatment, the longer the delay of symptom progression and the less overall financial cost.(17)

Presently, the only approved therapies for AD are the cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) and a N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)(memantine) receptor antagonist. While these agents are being used frequently, and for increasingly long periods of time, numerous areas of confusion exist about the clinical significance of their therapeutic effect, the importance of beginning early treatment, how or if you can combine treatments, and how treatment may impact outcomes or slow the progression of the illness. However, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine have not been well studied for use in outside Alzheimer’s and vascular dementias.

Common side effects caused by medications used to treat Alzheimer’s disease include dizziness, headache, constipation, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss/loss of appetite and confusion. At the same time, elderly patients often receive multiple medications due to an increasing number of acquired diseases. Certain drugs have adverse side effects on cognition due to interference with the cholinergic or GABA-ergic system.(26)

Other important issues with regard to medication use in the elderly are suboptimal dosing and polypharmacy. Suboptimal prescribing in older psychiatric patients causes iatrogenic morbidity, and is a potential source of decreased function in older patients with dementia,(27) i.e. the decreased functioning due to an inappropriate dose and not as a result of the disease. Medication side effects and drug-related problems caused by polypharmacy, can have profound medical and safety consequences for older adults and economically affect the health care system. The application of the Beers criteria and other tools for identifying potentially inappropriate medication use will continue to enable providers to plan interventions for decreasing both drug-related costs and overall healthcare costs.(28) The Beers Criteria uses 28 criteria describing the potentially inappropriate use of medication by general populations of the elderly as well as 35 criteria defining potentially inappropriate medication use in older persons known to have any of 15 common medical conditions.

Besides the current treatment options, meta-analyses have been conducted looking at emerging therapies of AD treatments. These therapies target a myriad of receptors and are attempts to treat symptoms and also be disease modifying. There is an acute need for new drugs and therapeutic approaches for treating Alzheimer’s, and also for improving the quality of cognitive function associated with normal aging and in many other disorders and syndromes that present with cognitive dysfunction. Compounds that act on allosteric sites on neurotransmitter receptors are expected to lead the field with new levels of specificity and reduced side effects.(29)

Used to treat the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, such as delusions, aggression, or hallucinations are atypical antipsychotic medications. However, while antipsychotics can benefit some patients, they appear to be no more effective than a placebo when adverse side effects are considered.(30) The use of atypical antipsychotics or “second-generation” antipsychotics for the treatment of behavioral symptoms in elderly patients with AD is not a FDA approved use for these agents. In 2005, the FDA issued a warning about the risks, such as cerebrovascular events, increased risk of diabetes and sudden death, associated with using antipsychotics in the elderly.

In the absence of approved agents, many physicians have turned to off-label use of both conventional antipsychotics and atypical agents.(31) “The evidence to support off-label use is limited and there are significant safety concerns, which include a doubling of mortality risk in this patient population," said Caleb Alexander, MD, MS of the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

The incidence of inappropriate use of antipsychotics seems to be highest in the nursing home environment. Serious safety concerns related to the use of antipsychotics have not decreased the prescribing of these agents to nursing home (NH) residents. A study completed by Chen Y et al, in January, 2010 found that more than 29% (n = 4818) of study residents received at least 1 antipsychotic medication in 2006. Of the antipsychotic medication users, 32% (n = 1545) had no identified clinical indication for this therapy.32 In addition, residents entering NHs with the highest facility-level antipsychotic rates were 1.37 times more likely to receive antipsychotics relative to those entering the lowest prescribing rate NHs, after adjusting for potential clinical indications (risk ratio [RR], 1.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24-1.51).(32)

Study results released from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness study for Alzheimer’s disease (CATIE-AD), on the effectiveness of antipsychotics to treat symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, underscore that AD is not just a neurological disorder of memory impairment, but has complex neuropsychiatric symptoms.(33) The first results of the CATIE-AD study confirm that available pharmacotherapy should target the balancing of the dopaminergic, serotoninergic, noradrenergic, excitatory and GABAergic neurotransmission by using antipsychotics, antidepressants, phase-prophylactic agents, and benzodiazepines. Antipsychotics that target multiple neurotransmitter systems show efficacy in treating behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), and are effective in controlling anger, aggression and delusions in Alzheimer's disease, while cognitive symptoms, quality of life and care needs are not improved.(34) “Neuropsychiatric symptoms are part of the disease course for Alzheimer’s disease patients. These symptoms increase the risk of institutionalization and, unfortunately, do not disappear when a patient is institutionalized,” said Christopher C. Colenda, MD, MPH, president of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, “Documenting efficacious and effective treatments is a critical area of research, and the importance of this study is that it mirrored real-world clinical practice.”

Psychosocial and behavioral interventions for the treatment of problem behaviors should be included as part of a comprehensive management program for patients and caregivers. Current treatment guidelines for behavioral symptoms uniformly stress that clinicians use nonpharmacological interventions prior to using medications.(35) Nonpharmacologic interventions that involve the family and community as well as the health care team foster a collaborative environment, that may help patients and caregivers to better cope with the troublesome symptoms associated with the disease. Interventions can include tactics such as music or art therapy, interaction through videotapes or even role-playing to acquire skills such as what to do in an emergency. Even creating a calm environment, void of loud noise or other assaults on the senses, can help to reduce or even eliminate the problem behavior.

The Alzheimer’s Association provides a brochure on Behaviors associated with the disease and suggestions for how they can be appropriately managed. In 1998, with a revision in 2003, the National Chronic Care Consortium and the Alzheimer’s Association published a brochure entitled, “Tools for Early Identification, Assessment, and Treatment for People with Alzheimer’s disease and Dementia,” (available at www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_toolsforidassesstreat.pdf) which offers advice on how to effectively manage patients with Alzheimer’s.

A series of well-designed cohort and case control studies have demonstrated that people with Alzheimer-type dementia do not complain of common physical symptoms, but experience them to the same degree as the general population. Patient assessments should therefore include the assessment of any behavioral changes caused by concurrent physical conditions and appearance of new features intrinsic to the disorder.(36) The British Medical Association, in cooperation with the National Health Service (NHS) Confederation developed quality measures for the treatment of dementia, inclusive of physical symptoms, and the suggestion that practices whose patient population includes many patients with dementia, develop a register of individuals so diagnosed. The measures are available at http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/browse/DisplayOrganization.aspx? org_id=1783&doc=8958#data

As there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, the goal of treatment is more focused on delay of progression of the illness and symptom management. Physicians, patients and families should discuss treatments goals related to preserving cognitive and functional ability, minimizing behavioral disturbances, and slowing disease progression, with maintenance of the patient’s, and care-giver’s quality of life.(37) The interpretation of goals differs between patients, caregivers and physicians. Patients and caregivers tended to identify solutions to specific problems (e.g., reduction in repetitive questions, decreased need for lists and routines) as targets for therapy, while physicians group many distinct problems under a single treatment goal of improved memory. In addition, patients and their caregivers set more goals than physicians did with respect to leisure, social interaction, behavior, and function.(38)

In the development of treatment plans for Alzheimer’s disease, improved communication and the development of treatment plans and goals that are in concordance with patient and families will be vital to the successful management of AD. Providing education to physicians on effective physician-patient interactions in the treatment of AD, and providing resources to care-givers can also help close the gap related to treatment goals.

“We need a fresh approach to figuring out how to manage these patients. This includes not only developing effective treatments for the underlying pathology of Alzheimer’s, but also, renewing efforts to study psychosocial and behavioral interventions, and alternative pharmacotherapeutic approaches to these symptoms. It is important to understand that many of these symptoms are transitory, and clinicians need a different mindset on how best to approach these difficult situations,” says Dr. Colenda.

The early identification of AD in primary care may reduce the rate of disease progression and delay placement in a nursing home,(4) but the role of the psychiatrist in the treatment of AD cannot be under estimated. Psychiatrists can have profound interpersonal effects on their AD patients, and the positive relationship with the psychiatrist may be a critical factor that influences the patient to accept treatment.(39) Collaboration between primary care and psychiatry can help to bridge gaps in understanding of disease progression and management, while also having a positive impact on patient outcomes.

With the elderly population of the United States slated to double in the next 20 years, and the rate of AD to quadruple in 40 years, vigilance for this disease and early identification is crucial, but prevention and health maintenance will undoubtedly also weigh heavily on the overall incidence for the disease. With increased recognition of symptoms in the early phase of the illness, and the development of treatment plans in concordance with patients and families, it is possible to delay disease progression and improve the quality of life for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and their families.

Do you have feedback for the author? Click here to send us an email.

Reference

- Kamat SM, Kamat AS, Grossberg GT. Dementia Risk Prediction: Are we there yet? Clin Geriatr Med 2010;26:113-123.

- What is Alzheimer’s? Alzheimer’s Association 2010. Available at http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp

- American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP). Psychiatry Conference to Focus on Medical Complexities of Geriatric Patients. Press Release 2010. Available at http://www.aagponline.org/news/pressreleases.asp?viewfull=141

- Reasons for the early identification of AD and MCI. Alzheimer’s Screen.com Available at http://www.alzheimersscreen.com/Earlierthebetter.htm

- Pike CJ, Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Barron AM. Protective actions of sex steroid hormones in Alzheimer's disease. Front Neuroendocrinol 2009;30:239-258.

- Vann RM. Effects of Stress on the Brain. Discovery Health Guide to Dementia 2008. Available at http://health.discovery.com/centers/brain-health/brain-disorders-conditions/dementia/stress.html

- Grant WB. Does vitamin D reduce the risk of dementia? J Alzheimer’s Dis 2009;17:151-159.

- Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:304-310.

- Dementia Symptoms: Brain exercises help reduce the risk. The Online Brain Games Blog 2010. Available at http://www.onlinebraingamesblog.com/online-brain-games/dementia-symptoms-brain-exercises-help-reduce-the-risks

- 4 Pillars of Brain Health. The Online Brain Games Blog 2010. Available at http://www.onlinebraingamesblog.com/brain-fitness/my-4-pillar-brain-health-goals-for-2010

- Mowszowski L, Batchelor J, Naismith SL. Early intervention for cognitive decline: can cognitive training be used as a selective prevention technique? Int Psychogeriatr 2010;1-12. [Epub ahead of print]

- Rolland Y, Abellan van Kan G, Vellas B. Healthy Brain Aging: Role of Exercise and Physical Activity. Clin Geriatr Med 2010;26:75-87.

- Weimer DL, Sager MA. Early identification and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Social and fiscal outcomes. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2009;5:215-226.

- Feldman HH, Pirttila T, Dartigues JF, Everitt B, Van Baelen B, Schwalen S, Kavanagh S. Treatment with galantamine and time to nursing home placement in Alzheimer's disease patients with and without cerebrovascular disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:479-488.

- Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, McRade T, Mastey V, Ieni JR. Donepezil Is Associated with Delayed Nursing Home Placement in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:937-944.

- Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR Jr, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology 2010;74:201-209.

- Doody RS, Geldmacher DS, Gordon B, Perdomo CA, Pratt RD, Donepezil Study Group. Open-label, multicenter, phase 3 extension study of the safety and efficacy of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2001;58:427-433.

- Neuroimaging monitors Alzheimer’s disease. Science News 2010. Available at http://www.upi.com/Science_News/2010/02/11/Neuroimaging-monitors-Alzheimers-disease/UPI-21411265896182/

- Alzheimer's Disease: Vitamin D, Curcumin May Help Clear Amyloid Plaques. Medical News Today 2009. Available at http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/157764.php

- New test predicts whether mild cognitive impairment will convert to Alzheimer’s disease. ScienceDaily 2009. Available at http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090316133427.htm

- Shaw LM, Venderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W,Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol 2009;65:403-413.

- Mild Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer’s Association 2009. Available at http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_mild_cognitive_impairment.asp

- Smith GE. Early-onset Alzheimer's: When symptoms begin before 65. MayoClinc.com 2009. Available at http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/alzheimers/AZ00009

- National Institute on Aging. What causes AD? Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center (ADEAR) 2010. Available at http://www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers/AlzheimersInformation/Causes

- Koedam EL, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YA. Early- versus Late-Onset Alzheimer's Disease: More than Age Alone. J Alzheimers Dis 2010. [Epub ahead of print]

- Weih M, Scholz S, Reiss K, Alexopoulos P, Degirmenci U, Richter-Schmidinger T, Kornhuber J. Usage of drugs with potential adverse effects on cognition in a memory-clinic. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2009;77:523-527

- Chan VT, Woo BK, Sewell DD, Allen EC, Golshan S, Rice V, Minassian A, Daly JW. Reduction of suboptimal prescribing and clinical outcome for dementia patients in a senior behavioral health inpatient unit. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:195-199.

- Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean R, Beers MH. Updating the Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Results of a US Consensus Panel of Experts. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2716-2724.

- Buccafusco JJ. Emerging cognitive enhancing drugs. Expert Opn Emerg Drug 2009;14:577-589.

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Use of Antipsychotics in Alzheimer’s Patients May Lead to Detrimental Metabolic Changes. Science Update 2009. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/science-news/2009/use-of-antipsychotics-in-alzheimers-patients-may-lead-to-detrimental-metabolic-changes.shtml

- Cassels C. Inappropriate Use of Antipsychotics in the Elderly Continues Despite FDA Warnings. Mescape Medical News 2010. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/715257

- Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, Tjia J, Lau DT, Gurwitz JH. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:89-95.

- McDuffie K, American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP). New Research, New Treatment Needed for Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease. Press Release 2006. Available at http://www.aagponline.org/news/pressreleases.asp?viewfull=110

- Kálmán J, Kálmán S, Pákáski M. Recognition and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementias: lessons from the CATIE-AD study. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung 2008;10:233-249.

- Alzheimer’s Association. Treating Alzheimer’s. Behavioral Symptoms. Available at www.alz.org/professionals_and_researchers_behavioral_symptoms_pr.asp.

- British Medical Association (BMA). Quality and outcomes framework guidance for GMS contract 2008/09. London (UK): British Medical Association, National Health Service Confederation; 2008:148.

- Geldmacher DS. Treatment Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease: Redefining Perceptions in Primary CarePrim Care Companion. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;9:113-121.

- Rockwood K, Graham JE, Fay S. Goal setting and attainment in Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with donepezil. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:500–507.

- Howe D. Key Psychosocial Interventions for Alzheimer’s Disease - An Update. Psychiatry 2008;5:23-27.

|

|