|

Monitoring Mood During the Golden Years: Assessing Geriatric Depression Head-On

by Monique Johnson, MD, CCMEP

Persistent sadness in late life is not normal

Geriatric depression is not okay! Okay? Okay. Still, many people, even some clinicians, accept decreased mood in older patients as normal or as being of insufficient priority to warrant intervention. The belief that being perpetually unhappy is to be expected, given life's circumstances, is one of the great myths that undermines patient care for many patients with mental illness, in general, and for older patients, in particular. It also is a huge contributor to the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of depression in older adults. This article highlights key aspects of the assessment of geriatric depression in order to promote improved recognition and diagnosis in older patients who are at risk for developing or are suspected to have depression. An upcoming Compass Points™ article will focus on treatment aspects of geriatric depression.

Geriatric depression is common but often underdiagnosed (and undertreated)

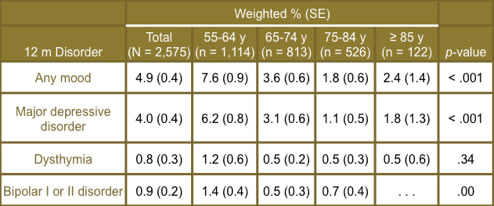

Prevalence estimates for major depressive disorder (MDD) in community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older are estimated at 3% in men and 4% in women.(1) Table 1 shows the overall and age-specific, 12-month rates for mood disorders for over 2,500 adults over age 55 in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) dataset.(2)

Table 1. 12-Month Prevalence Rates of DSM-IV Mood Disorders

in 2,575 Adults Aged 55 Years and Older (NCS-R).(2)

Despite its being common, the clinical detection of depression in older people continues to be a challenge. Garrard and colleagues completed a 2-year cohort study of older persons (n = 3,410) who took the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Approximately half of the respondents who had a GDS score of 11 or more (i.e., self-reported indications of depression) did not have documentation of clinical detection of depression by health providers. Men aged 65 – 74 years old and adults aged 85 or above were at highest risk for underdetection of depression by primary care providers. (3) Similar results have been seen among nursing home residents.(4,5)

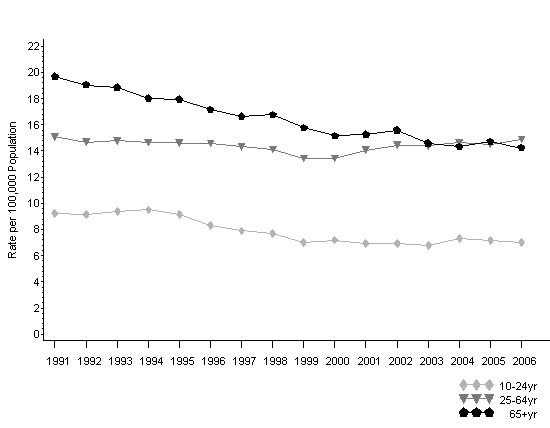

Left undetected and untreated, the consequences of geriatric depression are dire and include decreased quality of life due to higher mortality rates from both medical illness and suicide.(6,7) Suicide in this population is a real concern and is a major public health concern. Older adults have higher rates of completed suicide than any other age group in most countries of the world; older men are at greatest risk (see Figure 1).(8)

Figure 1. Trends in suicide rates among both sexes,

by age group, United States, 1991 – 2006.(8)

> Back to top

Steps can be taken to unlock the diagnosis

The Approach to Diagnosis

One key to improving diagnosis is to recognize that, while the DSM-IV-TR criteria for a depressive episode are no different for older patients than for all patients, the clinical presentation of a depressive episode is often different from that in younger adults.(9) Table 2 outlines some ways that older, depressed adults present for medical care and is expressed in terms of comparison with younger, depressed adults.(10,11) Awareness of these distinctions means that clinicians can use a "different eye" when they encounter patients who are at risk for depression.

Table 2. Presentation of Geriatric, Depressed Patients

Compared to That of Younger, Depressed Patients.(10,11)

- Mood symptoms are more likely to be hopelessness, weariness, and thoughts of death

- Patients have more complaints of pain and somatic symptoms (65% have hypochondriacal symptoms)

- Patients have more marked cognitive impairment, when it is present

- Patients more often have associated anxiety and agitation

|

Another clinical pearl is to be aware that older patients who are depressed often neither self-report nor seek treatment.(6,12) This ties back to the myth that decreased mood in older patients is to be expected, given their current stage of life. As such, a significant number of older adults minimize or deny depressed mood—in a behavior known as "masked depression"—and are less likely to verbalize emotions or feelings of guilt. This means that we, as clinicians, must be extra vigilant in our efforts to uncover depression when it exists in the population. Patients may not report it—we will need to ask.(12)

Differential Diagnosis

Perhaps one of the most important diagnostic challenges (and treatment challenges too) relates to the reality that certain medical conditions and some therapies used to treat them can mask or cause depression—and older adults have more medical comorbidities than younger adults do. Common, chronic medical conditions that that can lead to depression or make depression symptoms worse, often because they are particularly disabling, painful, or life-threatening, are diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, cerebrovascular disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, dementia, thyroid disorders, and malignancy. These common conditions are part of the differential list for older patients; many would be less likely to be included in the list for a younger adult.(12,13)

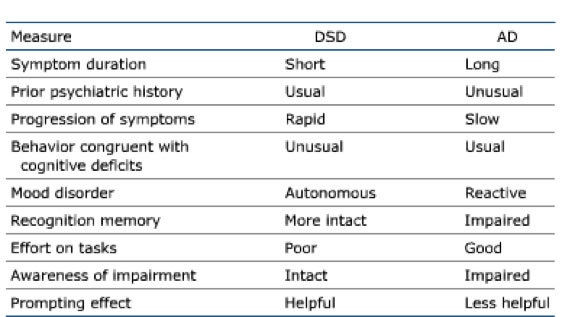

With respect to other major psychiatric conditions, the differential diagnosis of geriatric depression includes bereavement/adjustment disorder, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and psychosis.(13) The differential list for geriatric depression must also include neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia. While these two can be confused, there are distinctions that can assist in differentiating between them, as is outlined in Table 3.(14)

Table 3. Characteristics of Dementia Syndrome of Depression (DSD) Versus Those of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).(14)

Assessment: History, Physical Exam, and Psychiatric Interview

As in encounters with any patient with any suspected clinical condition, core assessment elements are history-taking and conducting a physical exam. For the older adult suspected to have MDD, clinicians should thoroughly evaluate cardiopulmonary and cerebrovascular status, as well as neurologic status. This strategy aligns with ruling in or ruling out key conditions on the differential diagnosis list. Additionally, a vigilant investigation of the patient's medications, including over-the-counter medicines and supplements, should be comprehensively undertaken because symptoms of depression are a side effect of many commonly prescribed drugs and older adults are more sensitive because aging causes less efficient drug metabolism. Some of the more common agents prescribed for and used by older patients that can cause or worsen depression include blood pressure medications, beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, sedatives, hypnotics, steroids, statins, pain relievers, anti-ulcer medications, and estrogens. This may mean that the extra efforts of getting a history from the spouse, partner, or family and of consulting the patient's pharmacist can be particularly useful.(11,12)

Assessment: Validated Clinical Questionnaires

Using measurement-based care (MBC) is extremely important in psychiatry and is endorsed as one of the overarching recommendations in the recent MDD treatment guidelines by the American Psychiatric Association (2010).(15) Specifically, the guideline reads:

"[Clinicians should] integrate measurements into psychiatric management [via] careful and systematic assessment of the type, frequency, and magnitude of psychiatric symptoms as well as ongoing determination of the therapeutic benefits and side effects of treatment. Such assessments can be facilitated by integrating clinician- and/or patient-administered rating scale measurements into initial and ongoing evaluation."

In geriatric depression, common, validated rating scales for mood symptoms include the above-mentioned Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)(16) and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D),(17) among others:

• The GDS is a 30-item questionnaire that queries for "yes" or "no" responses. One point is assigned to each confirmatory answer and then total points are summed; the resulting cumulative score is rated as 0 – 9 = "Normal," 10 – 19 = "Mild Depression," and 20 – 30 = "Severe Depression."(16)

• The HAM-D-17 is a 17-item, multiple-choice questionnaire with 3 – 5 possible responses per item. Eight items are scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 = "not present" to 4 = "severe." Nine items are scored from 0 – 2. Cumulative scores are rated using the following scale: 0 – 7 = "Normal"; 8 – 13 = "Mild Depression"; 14 – 18 = "Moderate Depression"; 19 – 22 = "Severe Depression"; and ≥ 23 = "Very Severe Depression."(17)

These are just two of the more commonly used scales; there are others. The important concept here is for clinicians to identify a validated tool that works best in their clinical setting, to become familiar with its use, and to systematically implement it as a routine practice strategy. For more information about depression rating scales, please visit the neuroscienceCME Communities of Practice webpage on MDD Rating Scales at http://www.neurosciencecme.com/resources_rating_scales_depression.asp.

> Back to top

Clinical Connections

- Depression in older adults is common, yet underdetected.

- Underdetection lends to undertreatment; left untreated, geriatric depression causes disability, decreases quality of life, and can lead to suicide.

- Older adults have higher rates of completed suicide than any other age group.

- Optimal diagnosis in older adults hinges on: 1) knowing how MDD presentation differs from presentation in younger adults; 2) considering the differential diagnosis; and 3) using validated assessment tools.

Recommended Review Articles on Geriatric Depression Assessment

• Small GW. Differential diagnoses and assessment of depression in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(12):e47. PMID: 20141704.

• Heok KE, Ho R. The many faces of geriatric depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(6):540-545. PMID: 18852559.

• Skultety KM, Rodriguez RL. Treating geriatric depression in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(1):44-50. PMID: 18269894.

> Back to top

Post-Compass Questions™

> Back to top

> Send feedback for the author

> View activity details

> Complete post-test/print CE certificate

References

1. Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(6):601-607. PMID: 10839339.

2. Byers AL, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE, Friedman MB, Bruce ML. High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):489-496. PMID: 20439830.

3. Garrard J, Rolnick SJ, Nitz NM, et al. Clinical detection of depression among community-based elderly people with self-reported symptoms of depression. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(2):M92-M101. PMID: 9520914.

4. Brown MN, Lapane KL, Luisi AF. The management of depression in older nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(1):69-76. PMID: 12028249.

5. Soon JA, Levine M. Screening for depression in patients in long-term care facilities: a randomized controlled trial of physician response. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1092-1099. PMID: 12110071.

6. Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(3):249-265. PMID: 12634292.

7. Beyer JL. Managing depression in geriatric populations. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):221-238. PMID: 18058280.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. National suicide statistics at a glance: trends in suicide rates among both sexes, by age group, United States, 1991-2006. CDC Website. http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/statistics/trends02.html. Reviewed September 30, 2009. Updated September 30, 2009. Accessed November 7, 2011.

9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (Text Revision) [DSM-IV-TR]. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

10. Devanand DP, Nobler MS, Singer T, et al. Is dysthymia a different disorder in the elderly? Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1592-1599. PMID: 7943446.

11. Heok KE, Ho R. The many faces of geriatric depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(6):540-545. PMID: 18852559.

12. Skultety KM, Rodriguez RL. Treating geriatric depression in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(1):44-50. PMID: 18269894.

13. Small GW. Differential diagnoses and assessment of depression in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(12):e47. PMID: 20141704.

14. Kasznial AW, Christenson DD. Differential diagnosis of dementia and depression. In: Storandt M, VandenBos GR, eds. Neuropsychological Assessment of Dementia and Depression in Older Adults: A Clinician's Guide. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1994: pp. 81–117.

15. Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, et al.; for the American Psychiatric Association [APA]. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd edition. APA Website. http://psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookid=28§ionid=1667485 - 654001. Published October 2010. Accessed November 7, 2011.

16. Mitchell AJ, Bird V, Rizzo M, Meader N. Diagnostic validity and added value of the Geriatric Depression Scale for depression in primary care: a meta-analysis of GDS30 and GDS15. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1-3):10-17. PMID: 19800132.

17. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. PMID: 14399272.

> Back to top |

|